The domes are transformed with technical wizardry to star as the ice palace of Bond villain, Gustav Graves.

The domes are transformed with technical wizardry to star as the ice palace of Bond villain, Gustav Graves.

Asked what makes a James Bond movie different and most people will say the visual style, the scale, the glamour, the gadgets and of course the exotic international locations. These motifs serve to enhance the dramatic narrative as well as reflecting the global reach of the 007 brand. So, in early 2001, whilst working on the film ‘Die Another Day’ (2002) with the Production Designer Peter Lamont, I was tasked with the brief to ‘recce’ for a spectacular location for the villain Gustav Graves ‘Ice Palace’. In keeping with the plot and the film holding many vignettes of previous films and Mythology Gags, the site of the palace was to be remote, spectacular and architecturally resonant in the filmic traditional sense. The scene was shot in Jokulsarlon in Iceland, however, key to the design was the ‘futuristic’ proposition in it being framed with the architectural ideas being pursued at the Eden Project, near St Austell, Cornwall.

The Eden Project domes are surrounded by a botanical garden © Hufton+Crow

The Eden Project domes are surrounded by a botanical garden © Hufton+Crow

During the production of the ‘The Rocky Horror Picture Show’ (1975) we placed a Buckminster styled geodeisic dome atop the Manor House tower. This was a intended as an allusion expressing the growing conflict between the past, represented by the historical artistic Gothic Manor House, and the science led future being agitated by the likes of Archigram and the seductive visioning of a neofuturistic project. A similar intended tension was envisioned to be generated from the juxtaposition of the modernist expressionistic foyer entrance and the emerging geodeisic styled biomes. Beyond that the design is an ‘homage’ to other architectural icons; merging elements of a Brasilia Bridge, the Sydney Opera House and JFK airport with the James T Baldwin inspired ‘Pillow Dome’ in the recently opened (2001), Eden Project. The framework structure and the argon filled laminated vinyl sheet (later to be ETFE) created a strong narrative and visually striking backdrop – now almost a sci-fi trope.

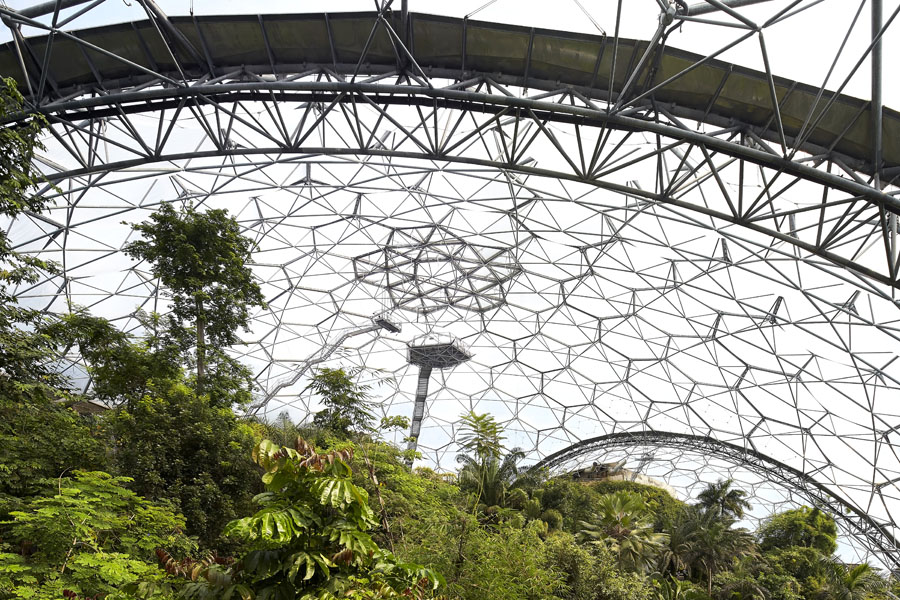

Inside one of the domes of the Eden Project © Hufton+Crow

Inside one of the domes of the Eden Project © Hufton+Crow

The recce to Cornwall proved pivotal for me, both as an inspiration for the film but also to wider concerns. For the film it was a zeitgeist moment, not merely reflecting the contemporary architectural step change but also giving the global audience a view of a new and destined to be icon. The prescient transformation of the Buckminster-Fuller geodesic dome into an ecological structure that is now globally acknowledged, ground breaking and internationally recognised is soon be joined by its twin Eden of the North in Morecambe, Lancashire.

The hexagonal inflated cells of the Eden Project © Hufton+Crow

The hexagonal inflated cells of the Eden Project © Hufton+Crow

The vision to take a disused china clay pit and transform it into the world’s largest greenhouse recreating the habitats from the deserts to the tropics was inspired. The four ‘biomes’, driven by ecological concerns at its heart, led to truly innovatory approaches just to service the needs of the different climatic zones with their highly individual planting. The project’s original mission and ambition to heal the land and create a unique culture comprising performance, educational and artistic spaces has extended well beyond its initial iterations. Today the entire site has been transformed into an extremely verdant collection of flowers, plants and fruits unparalleled in the UK.

Inside the rainforest dome at the Eden Project

Inside the rainforest dome at the Eden Project

For me this is how architecture should not be seen as just an expression of the built environment, a landmark, but one that is built to last with purpose, bettering and healing the landscape, leading, to shape and enhance people’s lives.