If you want to convert a sceptic to Modernist architecture, this is surely the British building to seduce them.

In hostile eyes, Modernism can be seen as an extrapolation of the factory, the hospital or the barracks, but here the dream takes flight and the De La Warr Pavilion is better seen as a temple – more precisely, a temple to Persephone, the goddess of spring, whose gigantic statue, by the sculptor Frank Dobson, was supposed to stand on the terrace, looking out to sea.

Erich Mendelsohn created the north face of the Pavilion as a long screen that hides what lies beyond. Entering from the street, light ahead lures the seeker but the view is veiled by the magnificent spiral stair. When you reach the first floor, you turn to face the ocean, usually sparkling with light, turning the Pavilion less into an object to be looked at than a frame to look out from.

An early postcard showing the Pavilion ©Kevin Lane

An early postcard showing the Pavilion ©Kevin Lane

The De La Warr Pavilion

The De La Warr Pavilion

The stunning spiral staircase at the De La Warr Pavilion and the plate commemorating the 1935 opening

The stunning spiral staircase at the De La Warr Pavilion and the plate commemorating the 1935 opening

The De La Warr Pavilion

The De La Warr Pavilion

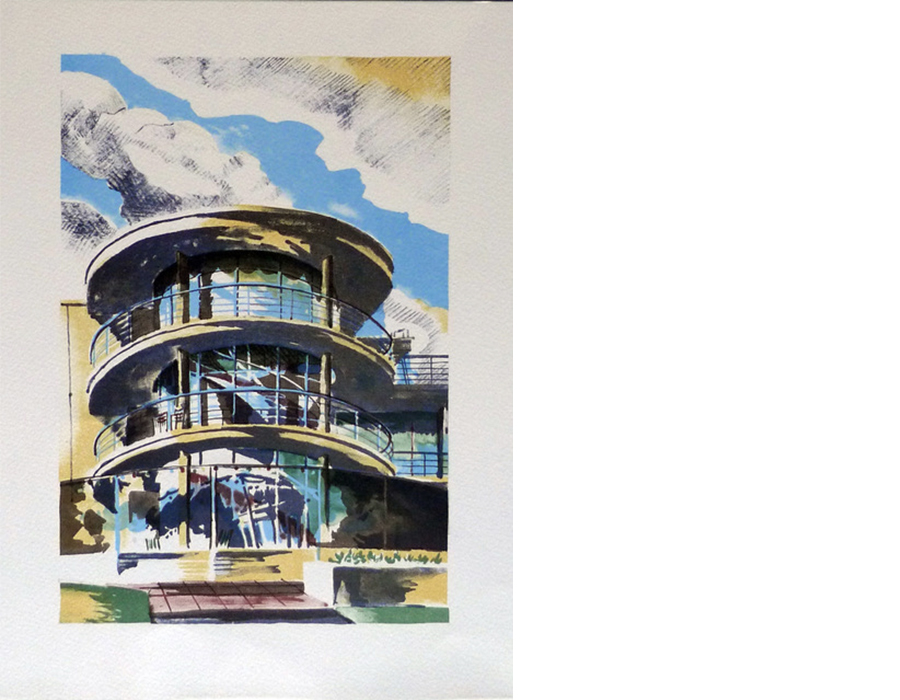

I knew the building by repute, but first came here in 1986 when I was finding locations for a series of ‘Seaside Lithographs’, eight artists’ prints published by the Spectator. Then aged 50, the goddess was almost charmingly dowdy with flock wallpaper and fake Cotswold stone bar fascias inside, while my print tries to capture the inauthentic chequerboard tiles on the columns supporting the staircase. Later, she had an extensive beauty-treatment and recovered her youth. High-maintenance she may be, but she brings millions into the local economy.

I had the good fortune to be involved in staging three exhibitions here. The first was on Serge Chermayeff, Mendelsohn’s architectural partner, who took care of the internal features of the theatre, café (with a dance floor and a mural by Edward Wadsworth), and a public library upstairs. Chermayeff believed in comfort of the body and soul, and to sit in one of the sprung-seat ‘Plan’ reclining chairs that originally furnished the library, or one of the colourful Alvar Aalto chairs that, rediscovered and reconditioned, can still be found here, was to enjoy both simultaneously. The second and third exhibitions were also connected to the Pavilion’s story. Mind into Matter commemorated the 175th anniversary of the Royal Institute of British Architects with eight selected buildings whose dates fell at 25 year intervals between 1834 and 2009.

The De La Warr Pavilion. Lithograph by Alan Powers

The De La Warr Pavilion. Lithograph by Alan Powers

Since 1934, the year that the Pavilion project began, was at the 100-year point, it was obvious to represent the building as itself, albeit with drawings and documents. Finally, in 2014, Jane Won, the Curator, invited me to work with Serge’s son, Ivan Chermayeff, on an exhibition of his posters and collages, work done for fun in a 60-year career as one of the USA’s top graphic designers. Ivan’s son Sam designed the installation in the ground floor gallery, and the day after the opening he went back to his pre-war childhood home, Bentley Wood, where he was photographed sitting in the lap, not of Persephone, but of Henry Moore’s Hornton stone Recumbent Figure, 1938, now in the Tate Collection.