I love hanging around in a good department store. Their era is almost played out now, and only the poshest or cleverest survivors seem to have a secure future. But proper shopping trips were once unthinkable without a sociable drift around the local retail titan.

Bentalls of Kingston upon Thames was mine. This was where it dawned on me that big, complicated spaces have to be designed. If they’re any good, of course, they take on an erratic life of their own. Bentalls typified the genre so patently that it was the cover star of the 1973 Ladybird Books primer, In a Big Store. Maurice Webb’s tremendous 1935 frontage is brazenly modelled on Christopher Wren’s Baroque parts of nearby Hampton Court Palace: long runs of tall, elegant windows with circular ones above, big white quoins, and so on. Customised with Eric Gill reliefs and an absolutely huge, carved BENTALLS set into the brickwork on high, it booms elegantly about its importance to Kingston. It’s wonderful, shameless and – let’s face it – a bit pompous.

Bentalls today, with the retained façade.

Bentalls today, with the retained façade.

This splendid rationalization of Frank Bentall’s constantly expanding Victorian draper’s shop was naturally designed to impress. The main lobby drew shoppers to a glass-roofed, galleried hall featuring the first ever British-made escalators. The deluxe fixtures and fittings were thriftily acquired in the liquidation sale of the opulent Oxford Street branch of Gamages, which had just opened and closed in the space of six months.

The new Bentalls Centre atrium.

The new Bentalls Centre atrium.

As a local 1970s kid steeped in both, I found Bentalls far more compelling than Hampton Court. While Mr Cole tended to my dad’s hair on the ground floor, in a gentlemen’s enclave little changed since the 1930s, I set about my important browsing business. In forty minutes, I could cover Toys, Books, Sports and Records, and be back nursing an ice cream float in the Silver Café (where I was meant to have stayed put the whole time), staring out innocently at Clarence Street. No need to consult the store guides at the foot of each escalator – I knew my routes. Each department was a discrete, expert world but everything, you sensed, was united. Bentalls staff badges and paper bags, Bentalls tannoy announcements (“Bentalls calling!”), Bentalls warehousemen in buff coats coming and going via their own mysterious networks.

Hoardings covered in advertisements harking back to Bentalls early years.

Hoardings covered in advertisements harking back to Bentalls early years.

The grand exterior petered out halfway down Wood Street into to an earlier mock-Tudor stretch of blackened wood and hung tiles. This was my favourite way in, offering a hazier idea of what lay beyond that was hard to map on to the monolithic outside view. Somehow it felt like the ‘wrong’ entrance. Lower ceilings; a broad, creaking oak staircase to the restaurants, The Mulberry Tree and The Thames Room; the Wolsey Hall (more reflected Hampton Court glam) for special displays; a corridor to the Gents hung with painted panels naming staff lost in two world wars. Different heights, different smells, different zones. It was all a spell, really; a highly faceted idea of how shopping ought to be, already a little ragged at the edges in my day.

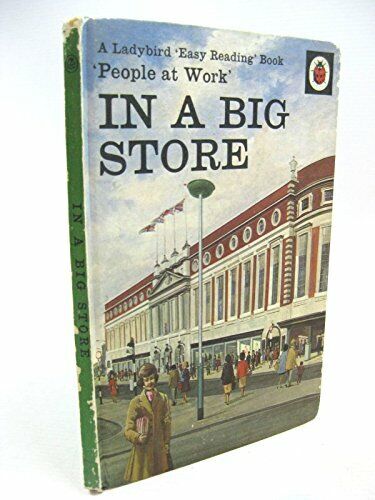

In a Big Store published in 1973 was the last book in the Penguin series and featured the facade of Bentalls on the front cover. All illustrations were by John Berry © Penguin

In a Big Store published in 1973 was the last book in the Penguin series and featured the facade of Bentalls on the front cover. All illustrations were by John Berry © Penguin

At the end of the 1980s, the whole place was demolished, leaving only that defining Maurice Webb frontage – a truly audacious act of facadism. A massive shopping centre went up behind it, and a rather less charismatic new Bentalls store behind that. It was a bold try by the company to move with the times, but it sacrificed every accretion of careful progress since 1867.

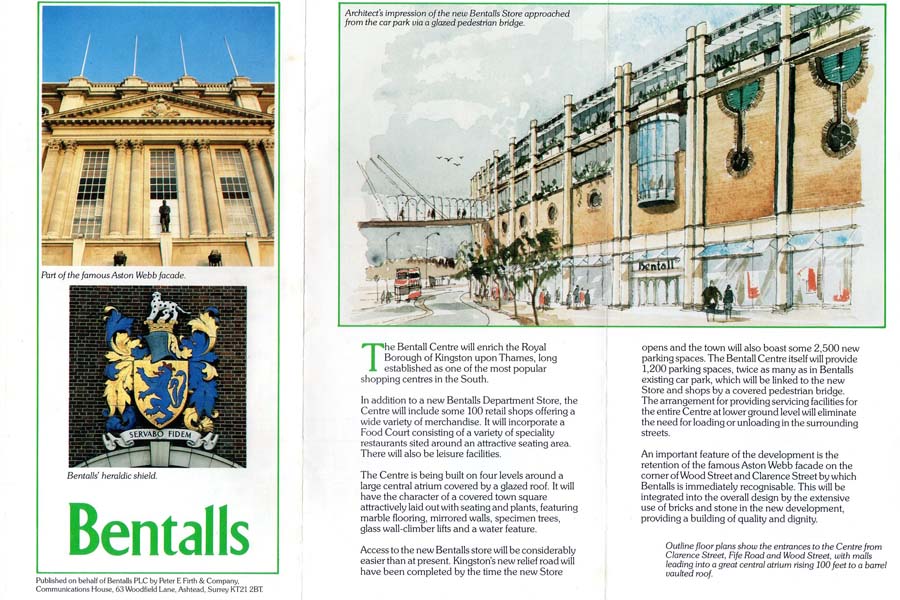

Leaflet outlining the plans for the new department store.

Leaflet outlining the plans for the new department store.

At least the original Bentalls, along with my unreliable memories, was spared the long uncertainty now being visited on ailing department stores everywhere. After decades of centrality, the fight is on simply to preserve and repurpose their remains. If you’re old and sentimental enough, it feels abrupt – and a little sad.