...But just as we can move mountains when out liberties are threatened and we will have to fight for our lives, so can we when the future of our London is at stake.

Lord Latham, Labour leader of the LCC at this time, in his foreword to the Plan.

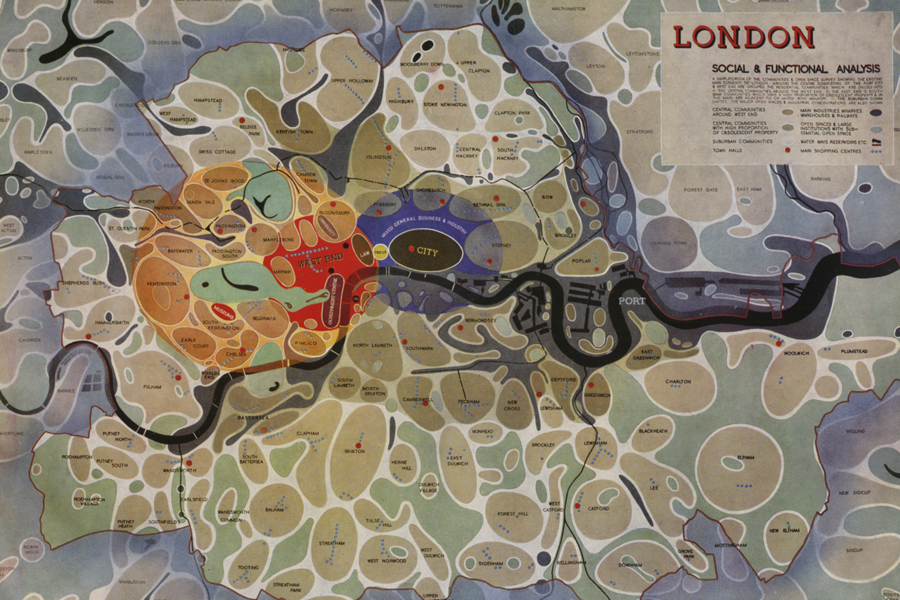

Social and Functional analysis of London from the Abercrombie Report

Social and Functional analysis of London from the Abercrombie Report

When I was asked to pick my favourite building for this project, I chose instead a masterplan – the 1943 Plan of the Social and Functional Groupings of London. Conceived by planners Sir Leslie Patrick Abercrombie and John Henry Forshaw, and illustrated with striking clarity by Arthur Ling, the diagrammatic plan shows London’s distinct, yet interdependent urban villages and industrial districts arranged around the capital’s historic hearts, the West End and the City. Obviously, the Plan is not a building, but I chose it because good architecture begins by responding to its social and physical context.

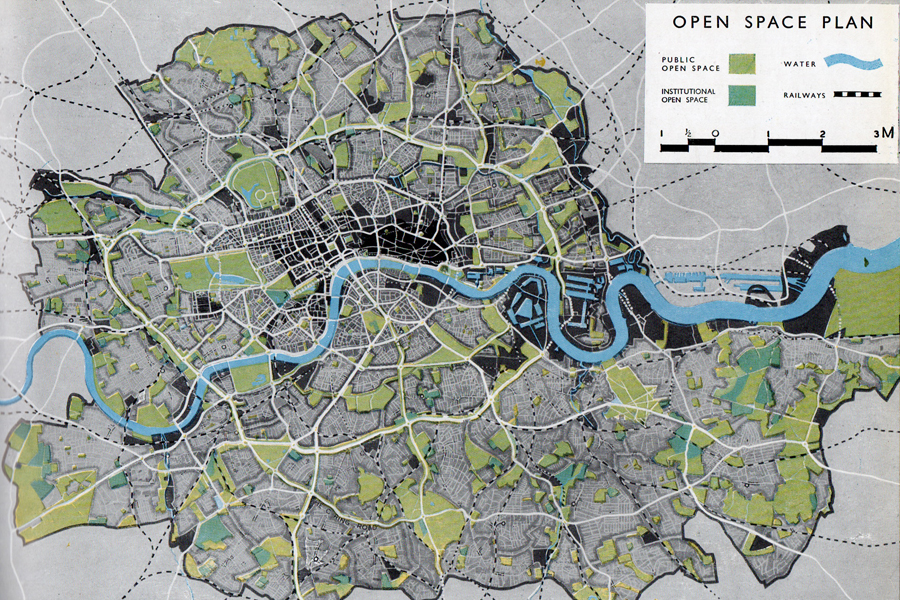

Open Space Plan of London from the Abercrombie Report

Open Space Plan of London from the Abercrombie Report

Working as part of the London County Council, Abercrombie and Forshaw developed the plan to help with the reconstruction of London after the anticipated end of the Second World War. Their ‘Social & Functional Analysis of London’ remains one of the most iconic maps of London. In particular, the development of open spaces was of high importance to Abercrombie, from city squares to formal greens and the green belt. Most importantly, both Abercrombie and Forshaw saw the plan as ‘an idea, something that is living, something that is growing.’ This highlights the inherent flexibility and responsiveness that characterised the Plan and its goals, underlining the city (in this case London) as a living, breathing entity that responds to the needs of its citizens.

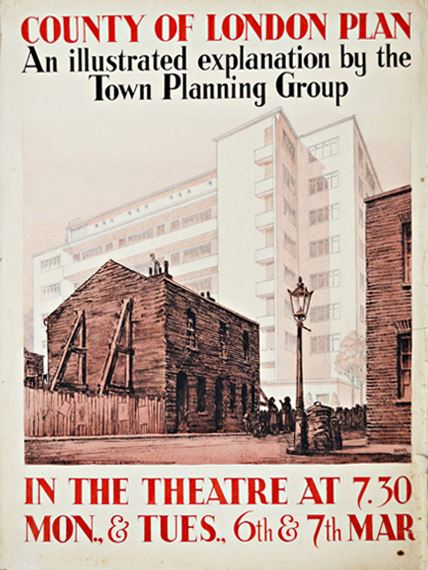

This poster appeared in Stalag III inviting prisoners of war to a talk around the London Plan, an insight into the importance of the report.

This poster appeared in Stalag III inviting prisoners of war to a talk around the London Plan, an insight into the importance of the report.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, being shown a model of London as part of an exhibition in County Hall © S Hawking

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, being shown a model of London as part of an exhibition in County Hall © S Hawking

The map depicts London as an agglomeration of neighbourhoods, each delineated and anchored by a high street as its commercial centre. Post- Covid, we can learn from their ideas, developing fresh approaches to the way people live in major cities, reducing the impact of the car and further greening the city. In today’s popular parlance, this is what is known as the 15-minute city. Everything a person needs: from homes to workplace; from shops and entertainment venues to schools and medical centres – they are all contained within an easy walking distance.

An imagined street scene © Foster + Partners

An imagined street scene © Foster + Partners

Today, 90 per cent of London’s population still lives within a ten-minute walk of a high street. An integral part of Abercrombie’s famous map, the high street continues to be the backbones of many of our communities, illustrating the resilience of urban systems. While the pandemic has accelerated the decline of several local high streets, the concomitant working from home revolution could become the catalyst for its revitalisation. The empty properties on high streets could become a new breed of community co-working spaces and other support functions to provide a much-needed change of scene from working in our homes. Until the architecture of homes catches-up with our newfound flexible working arrangements, a diffuse network of small-scale co-working spaces could become the new high street flagship store, allowing residents to work and play locally. This could be enhanced by re- evaluating residential streets with new ways of handling residential cars to provide more space for landscape, people and bikes. This would go some way towards transforming sleepy residential enclaves and dusty high streets into vibrant mixed-use neighbourhoods.